Riichi mahjong is a variant of mahjong created and popularized in Japan. Mahjong is a family of tile-based games where the goal is to create a winning hand containing specific combinations of tiles, either by drawing them from the tile wall or by calling them from other players. Mahjong shares some similarities with rummy games, and if you’ve played rummy before the goal of creating runs and sets may already be familiar to you. Riichi mahjong involves an engaging mix of luck, strategy, and skill, and if it sounds interesting to you, please read on and learn a little more about the game (or just jump in and try it).

Brief cultural context

Mahjong was developed in China in the 19th century. There are a number of Chinese mahjong variants, including Chinese classical mahjong, Sichuan mahjong, and Hong Kong/Cantonese mahjong. In the 1920s, mahjong was imported to the United States (by way of an oil company representative who played while living in China) and to Japan (by way of a soldier named Saburo Hirayama). The American variant was eventually standardized in 1935 when the rules were simplified and codified, and is now commonly referred to as Mah-jongg. In Japan, Hirayama started a mahjong club, parlor, and school in Tokyo. The rules for Japanese mahjong were initially simplified and then later made more complex before it evolved into modern riichi mahjong. This process of evolution also involved the creation of a number of regional variants.

Riichi mahjong is now the most popular table game in Japan, with millions of players and thousands of parlors (jansou). Japan also has a professional riichi mahjong scene, where professional players are part of a handful of mahjong organizations and participate in league play. This elevation of mahjong to the level of sport provides an alternative view on a game that tends to have a strong association with gambling in Japan, though of course, many do play for money, especially in jansou.

Recently, riichi mahjong has been increasing in popularity outside Japan in part due to its depiction in anime/manga (especially Saki and Akagi) and in video games (such as Final Fantasy XIV and Yakuza). Accessible online platforms for playing riichi mahjong, such as Mahjong Soul, have also contributed to its increasing popularity.

Playing the game

In a standard length game of riichi mahjong (a hanchan), game rounds start with East 1 through 4 then proceed to South 1 through 4. Four players are seated in the East, South, West, and North seats. The player in the East seat is the dealer (oya). The dealer earns more points for a win, and the current round repeats on dealer win. The seats rotate as rounds progress, so each player has a chance to be oya (that is, to be in the East seat) twice a game. A typical game of riichi mahjong has between eight and twelve rounds, though they can often go longer. Whoever has the most points at the end of the final round wins the game.

A round begins with the players shuffling a set of 136 tiles, then arranging them into a set of four walls two tiles high and 17 tiles long. After placing the walls, the dealer rolls a pair of dice to determine where the tile wall is broken, then each player takes tiles until they have 13 tiles as their starting hand. Seven tile stacks (14 tiles total) are marked for a special purpose and are known as the “dead wall,” and the remaining 70 tiles form the playing wall, where players draw from. Players then begin drawing tiles from the wall, starting with the dealer and moving counterclockwise, discarding a tile each time so that their hand remains at 13 tiles. Discarded tiles are placed in an ordered fashion, as required by the rules (using your opponents’ discards to glean information about their hand is also an important element of strategy).

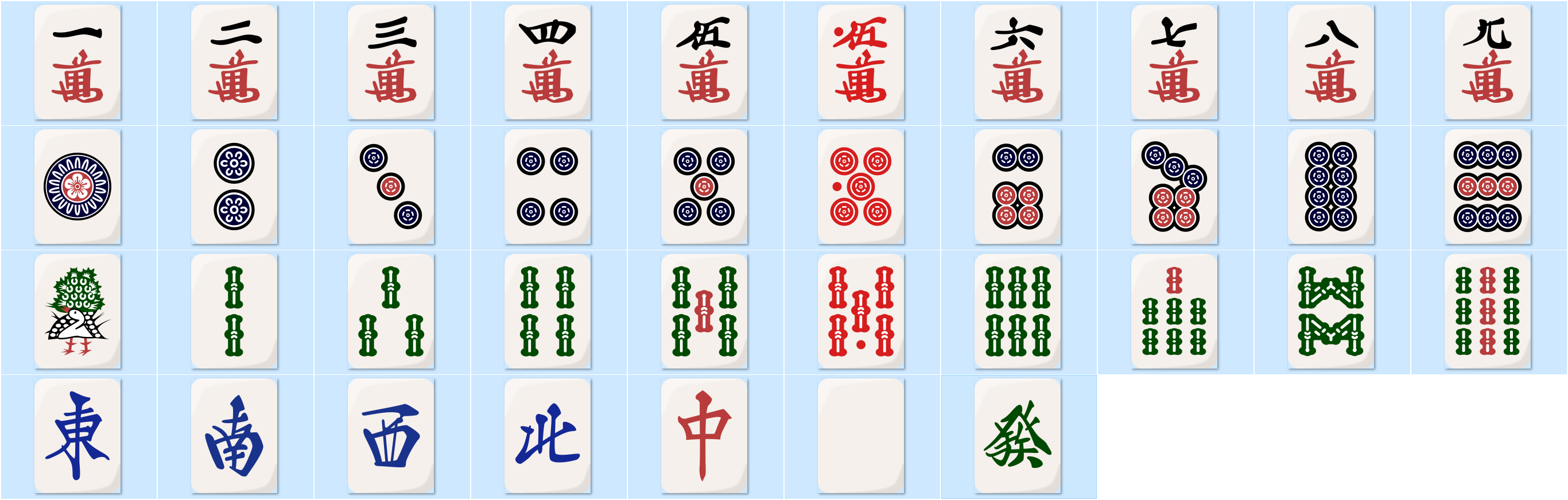

The set of tiles includes tiles of 34 types, with 4 tiles of each type. The 34 types of tiles are shown below, and consist of three suits of tiles numbered one through nine and then seven types of non-numbered “honor” tiles.

- First row: Character tiles (manzu): one through nine (including a special red 5-man)

- Second row: Dot tiles (pinzu): one through nine (including a special red 5-pin)

- Third row: Bamboo tiles (souzu): one through nine (including a special red 5-sou)

- Fourth row: Wind tiles: East (ton), South (nan), West (shaa), North (pei); then Dragon tiles: Red (chun), White (haku), Green (hatsu)

In each round of play, players will attempt to win a hand. To win their hand, a player needs to complete four groups (mentsu) and one head (atama, also commonly called a pair). Groups come in three forms:

- Run/sequence (shuntsu): A set of three consecutive numbered tiles. For example, 1-pin, 2-pin, and 3-pin, or 4-sou, 5-sou and 6-sou. Does not wrap around (in the standard ruleset).

- Set/triplet (koutsu): A set of three identical tiles.

- Quad (kantsu): A set of four identical tiles. Kans operate by special rules so that they are only counted as 3 tiles in the hand, and have other special properties as well.

In addition to having four complete groups and one head, a player must also have at least one yaku to win a hand. See the next section for a short discussion of yaku.

A player attempting to form groups and advance their hand only by drawing and discarding tiles is said to have a closed hand (menzen). In order to speed up their hand progression, a player may choose to open their hand by calling tiles from other players. The two most common calls are:

- Chii: A call to use a tile just discarded by our left player (kamicha) to complete a run in our hand. For example, if we have a 5-pin and 7-pin tile in our hand and our kamicha discards a 6-pin tile, we may call chii on that tile.

- Pon: A call to use a tile just discarded by any player to complete a set in our hand. E.g., if we have two haku tiles, we may call pon on a haku that was just discarded to complete a set of haku.

Chii and pon calls are made vocally by saying “chii” or “pon” upon seeing the discard. If you call pon, the general rule is that you must do so before the next player draws a tile into their hand. Pon takes priority over chii if both calls are made on the same discard. Called groups are set aside from your hand, face up and visible to other players (hence “open” hand). The upside of calling is that you can ensure you complete a group without having to rely on the luck of the draw. The downside of calling is that open hands have a significantly reduced number of available yaku, narrowing the ways you can win the hand. Note that there are also three variants of the Kan call, which forms groups of four tiles. See a more thorough game introduction for the rules for calling kan.

Once a player has advanced their hand to the point where it only needs one more tile to complete, they are said to have a ready hand, or to be in tenpai. A hand in tenpai will have three complete groups, a head, and one incomplete group, or it can have four complete groups and an incomplete head. For example, the following hand is in tenpai, and is said to wait on 2-pin and 5-pin, either of which would complete the 3-pin + 4-pin group and thus complete the hand.

A hand that is one tile away from tenpai is called iishanten or 1-shanten. A hand that is two tiles away from tenpai is ryanshanten or 2-shanten, and in general one that is n tiles away from ready is n-shanten. The general goal is to make your hand closer to ready by completing groups, while maximizing your hand’s tile acceptance (ukiere), or the number of tiles that will bring your hand one step closer to tenpai. The strategy involved in lowering your hand’s shanten while maximizing ukiere is generally referred to in English as tile efficiency, and it is a topic of considerable depth.

Finally, if a player has a hand in tenpai and has at least one yaku, they are in a position to win the hand. Since a hand in tenpai has 13 tiles and a complete hand has 14 tiles, a player can win on the final tile either when another player discards it or if they draw it themselves. This corresponds to the two calls:

- Ron: Calling a win when another player discards a tile that completes your hand.

- Tsumo: Calling a win when you obtain a tile that completes your hand by self-draw.

Like chii and pon, ron and tsumo calls are said out loud to alert the table that you have won the hand. Once calling ron or tsumo, you flip down the tiles of your hand so that the other players can confirm you indeed have a winning hand, and then the hand is scored (scoring can occasionally be complex and won’t be covered on this page). Once the hand is scored, points are redistributed accordingly, and the next round starts. If all 70 tiles of the playing wall have been drawn and discarded and no player has won a hand, the round is said to end in exhaustive draw (ryuukyoku).

This all seems like a lot of information just to get started, but I promise that the game and the general thrust of building and winning hands makes more sense in practice than it does in text. There’s no substitute for just trying it out! More detailed discussions, other aspects of the game such as defending against other players’ hands, and the full ruleset are much easier to grasp once you have wrapped your mind around the basic structure and flow of the game.

Additional rules

A full accounting of the rules of riichi mahjong and how they differ from other mahjong variants is outside the scope of this intro page. That said, four central and characteristic aspects of riichi warrant mention here.

Yaku

Yaku are specific hand patterns or game conditions and essentially act as “win conditions” in riichi mahjong. As stated in the previous section, a hand requires at least one yaku in order to win. The standard rulesets of riichi mahjong define 26 yaku, though there are also so-called “local” yaku that can be included in games using nonstandard rules. Experienced riichi players have the yaku memorized, but beginning players usually learn a few important and common yaku to start and incorporate more into their play as they gain experience. Yaku are worth varying amounts for the purposes of scoring, and generally the more valuable ones are harder to achieve. We recommend new players consult a yaku list, but we will point out a number of them that beginning players should know.

- Riichi: See next subsection. The most important yaku in the game.

- Menzen tsumo: Winning a closed hand by tsumo counts as a yaku, meaning closed hands always have one potential yaku available even without riichi.

- Yakuhai: Having a set of dragon tiles, seat wind (jikaze) tiles or round wind (bakaze) tiles gives a hand yaku. For example, a player sitting in West can get yakuhai by having three west wind tiles (seat wind) and a player can get yakuhai by having a set of south wind tiles during South 3 (round wind). A hand can have multiple yakuhai and is scored accordingly. Yakuhai is available to open hands, and along with tanyao, is the most common way for open hands to have yaku.

- Tanyao: Having a hand composed entirely of “simples”, suited tiles between 2 and 8, grants tanyao. Since this yaku is available to open hands, open tanyao is an extremely common hand in riichi mahjong (except in rulesets where it is forbidden).

- Toitoi: Having a hand of four sets/triplets plus a pair gives toitoi. Available to open hands, so players may pon to build toitoi hands.

- Chiitoi: One of the few yaku that counts as a special exception to the four groups plus a head hand composition rule, a chiitoi hand consists of seven pairs. Must be closed, by definition.

- Honitsu: Having a hand composed of honor tiles plus tiles of only one suit gives honitsu. Honitsu is available to open hands, but is worth fewer points in that case.

- Chinitsu: Having a hand composed entirely of tiles of a single suit gives chinitsu. Similarly to honitsu, is worth fewer points when open.

In addition to the standard yaku, riichi mahjong includes a set of special, extremely valuable hands called yakuman. These are rare hands that generally involve a good deal of luck to obtain. You can see a list of yakuman hands here. Due to their showy nature and enormous value, these are highly sought-after hands, but we don’t recommend beginning players worry so much about them to start.

Riichi

The namesake of riichi mahjong, riichi is a both declaration and a bet a player can make with a closed tenpai hand that also serves as a yaku for that hand. When a player with a closed hand reaches tenpai upon drawing a tile, they may declare riichi by saying “riichi,” discarding an unnecessary tile placed sideways into their discard pool, then placing a thousand point stick into the center of the table. That player can no longer modify their hand for the rest of the round (with one exception for certain kan calls), and can call ron or tsumo when appropriate. In other words, a player who declares riichi will then immediately discard each tile they draw unless it is a winning tile. Declaring riichi sacrifices flexibility for:

- Riichi (the yaku): The bet itself counts as yaku, so riichi provides a way for a closed tenpai hand to win even if there are no other yaku present.

- Ippatsu: A yaku only available to players who declare riichi, ippatsu adds value to the hand if it is won within one turn, provided no other calls at the table interrupt (or “break”) it.

- Uradora: See next subsection.

- Intimidation: Declaring riichi alerts other players at the table that you are ready to win. This may cause other players to shift to defensive play, or to “fold” to your hand.

Riichi is a powerful tool, and it is often (but not always) better from an expected value standpoint to declare riichi with a closed tenpai hand than to not, even if the hand has other yaku. The value riichi adds to a winning hand is frequently worth the cost even if the yaku it grants is not necessary. Declining to declare riichi with a closed tenpai hand is referred to as keeping damaten, or simply dama. Players may opt to keep dama if they are seeking to upgrade their wait, or if they think they will have a better chance at winning by not annoucing that they’re tenpai to the table. The merits of riichi vs. dama vary by situation and seasoned players often disagree.

Dora

Dora are tiles that grant a winning hand additional value (a higher score) if they are included. At the start of each round, a specific tile in the dead wall is flipped face-up and acts as the dora indicator. The tile after this tile in the tile sequence is now a dora tile. With the suit tiles, this is straightforward (note that this does wrap around: 9-man as the indicator tile means 1-man is dora, and similarly with the other two suits). With the honor tiles, winds go in round order: East -> South -> West -> North -> East, and dragons are ordered Haku -> Hatsu -> Chun -> Haku. In addition to this standard type of dora tile, there are three additional types of dora tile in riichi mahjong:

- Akadora: Commonly known in English as “red fives,” in many riichi rulesets, one tile each of 5-man, 5-pin and 5-sou is replaced with a special red variant that acts as dora. The rule that includes akadora is called aka ari, and if they are not included, it is aka nashi.

- Kandora: When a player calls kan, an additional dora indicator is flipped over in the dead wall, introducing a new dora tile into play. Kandora are otherwise identical to standard dora.

- Uradora: When a player wins a hand after declaring riichi, the tiles in the dead wall underneath revealed dora indicators act as additional dora indicators for the purposes of scoring that hand. These tiles are only revealed upon a win, so you can’t know what tiles are uradora beforehand. Normally, that means riichi hands have access to one (potential) additional dora tile. However, if several dora indicators are revealed due to kan calls, this applies to each one. For example, with one kan call, a winning riichi hand will be scored based on two normal dora indicators and two uradora indicators. Uradora act as an incentive to declare riichi.

Because many high value yaku are difficult to build and win with, dora often act as a crucial source of hand value in riichi mahjong.

Furiten

Furiten is a rule that places a restriction on what tiles a ready hand may win on by ron. A hand in tenpai is in a state of furiten and cannot win by calling ron in the following cases:

- At least one winning tile is in the player’s own discard pool (this includes tiles called from the player, even if they are no longer technically in this discard pool)

- The player with the hand in tenpai has declared riichi and passes on a winning tile

- The player with the hand in tenpai who has not declared riichi (is either open or keeping dama) passes on a winning tile discarded by another player

Note that cases 1 & 2 induce a state of persistent furiten that lasts until the end of the round, while case 3 induces a state of temporary furiten that lasts until that player’s next turn. A hand in furiten may still win by tsumo, provided the hand has yaku (since menzen tsumo is a yaku, closed hands may always do this).

The furiten rule is the foundation of defensive play in riichi mahjong and is the primary reason the discards are ordered and segregated in riichi rather than unordered like in some other mahjong variants. Knowing that a player cannot call ron on any tile that they have previously discarded gives other players a chance to avoid dealing in to their opponents if they declare riichi or are displaying a high value hand.